Dark Side of Delivery: The Growing Threat of Bioweapon Dissemination by Drones

Add bookmark

Drones represent a new challenge for the counter-terror and counter-biological weapons community. They can be deployed to delivery and disseminate biological and chemical materials in acts of agricultural terrorism; recent incidents involving gangs in China demonstrate the viability of this method. The following article explores this issue in more detail and considers what steps need to be taken to bring this international challenge to light.

Biological weapons (BW) are essentially comprised of (1) a weaponized agent (e.g., a microbe, toxin, or device), and (2) a mechanism/system for delivery and/or dissemination. While several technologically advanced countries (e.g., the U.S., China, Russia) have industrialized BW programs, BW production and delivery have remained challenging for rogue developing nations and non-state actors.

However, the advent of extant and emerging enabling technologies could make BW production and dissemination easier and faster. Exemplary of such facilitated means of production is the use of gene-editing tools and techniques such as CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats).

These could be employed to (1) modify existing microbes and toxins to increase their pathologic and/or lethal characteristics; (2) alter the stability and/or durability of existing agents to enable extended periods of delivery and dispersal; and (3) create pathologically disruptive or destructive agents anew.

Agricultural Terrorism: A Case Study in Bioweapons Drone Delivery and Dissemination

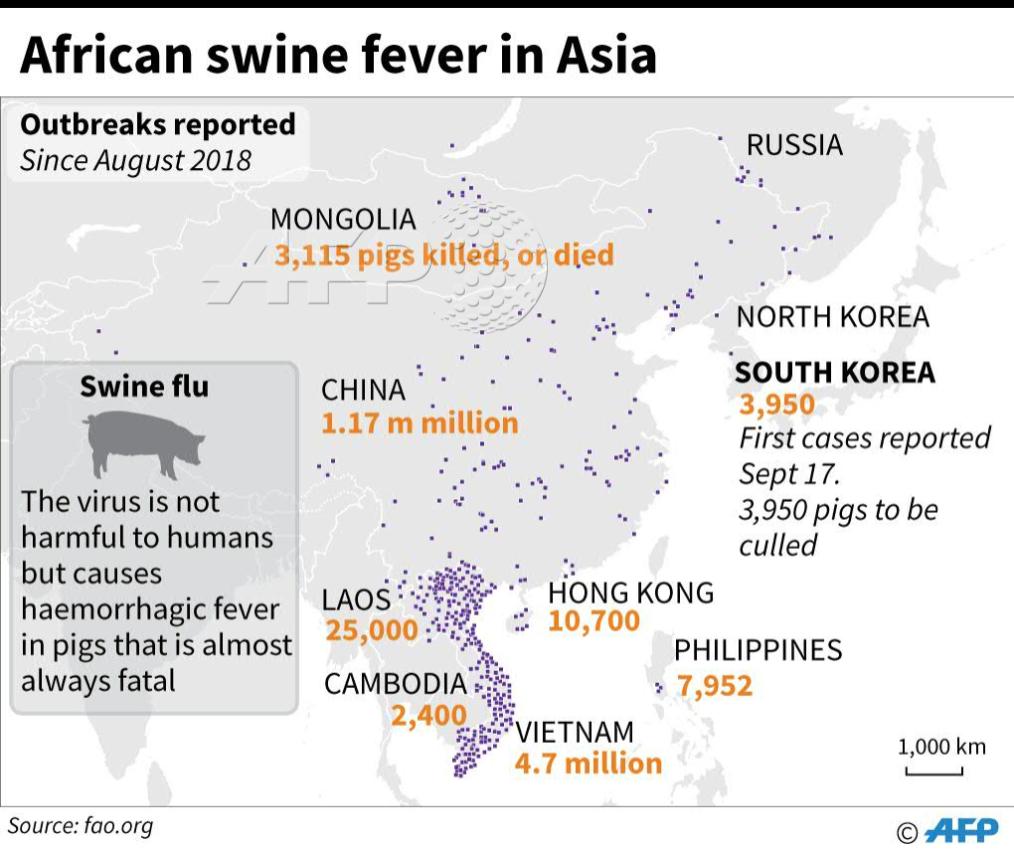

The use of drones could meet the challenges of delivery and/or dissemination. A recent article in the South China Morning Post reported that Chinese gangs are using drones to spread African swine fever in pig populations, infecting and subsequently killing several herds, and furthering the spread of this pathogen across Asia. The article quotes a local farm manager:

“One of our branches once spotted drones air dropping unknown objects into our piggery, and later inspection found [the] virus in those things”

Although the virus has not infected humans, the contagion has created a food shortage in the region and disrupted international pork markets. As well, Chinese gangs are utilizing misinformation campaigns to foster public fears about – and reactions to - the spread of the disease. These efforts have instigated farmers to sell their pigs at discounted rates to the gangs that then sell those hogs for a profit.

Local husbandry and veterinary bureau workers in protective suits disinfect a pig farm as a prevention measure for African swine fever, in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, China, August 2018. (REUTERS/Stringer)

This is blatant agricultural terrorism: an act that affects the food and produce resources of a nation or region to incur ecological, public health, and economic instabilities, and thereby generating public unrest, disrupting financial infrastructures, and threatening national security.

Additionally, purloining a region or nation’s livestock and plant resources can lead other countries (i.e., that are free of the infection) to impose lace restrictions, sanctions, or total trade moratoria on these, thereby incurring losses in local and/or global trade and revenues. This has not gone unrecognized, as such agriculturally-focused engagements are of known interest to a number of terrorist networks (e.g., al-Qaida).

It is in this light that we express our growing concerns about the use of drones to effectively deliver and disperse BW. Our consternation reflects the view of Dennis M. Gormley, Professor of Public and International Affairs at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for National Preparedness that, “most unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) …have ‘long wings’ and you can strap anything to them.” As Joshi and Stein have noted, drones could increase the BW delivery and dissemination by a factor of ten.

Global Drone Proliferation and Weapons of Mass Destruction

Utilizing drones would also limit the cost, expertise, and testing required for BW delivery (if/when compared to the use of bombs, missiles, or large area spray apparatus). We envision a scenario in which an actor(s) could use drones to deliver and disseminate some (highly morbid or perhaps lethal) BW to relatively small numbers of select but sentinel groups (of livestock, plants, or humans).

This effort could be paired with both an aggressive misinformation (social and public) media campaign and subsequent use of a limited number of (non-BW carrying) drones to evoke public fears and disrupt populational lifestyle, security, and functionality.

The increasing availability, facility, and employment of drones – in various applications - exacerbates both the potential for their malicious use, and justifiable concerns. Gormley asserts that “the problem is… creating an international norm” and countries continue to implement drones within their military arsenals. We concur, having previously noted that the use of unmanned vehicles may affect both thresholds and tolerances for hostile acts.

It was announced in January 2020 that Maj. Gen. Sean Gainey will lead a 60-person team for the Pentagon's new Counter-UAS office.

Recently, the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) – the principal agreement for governing missiles, drones, and associated technologies – held its 32nd Plenary Meeting in Auckland, New Zealand in early October 2019. The primary purpose of the meeting was to “review and evaluate the MTCR’s activities … and to advance the efforts of [State] Partners to prevent the proliferation of unmanned delivery systems capable of delivering Weapons of Mass Destruction (nuclear, chemical and biological weapons).”

Countries adhering to MCR regulations heed a consensus-based export-control list that governs Category I devices, inclusive of UAVs capable of flying more than 300 km (~186 miles) and carrying a payload of 500 kg (~1102 lbs.). Yet, any actor seeking to obtain a drone and employ drones that do not exceed these limitations would not meet any significant challenge or restriction.9 Furthermore, it is essential to note that only 35 countries are members of the MTCR, and several developed countries (e.g., China and Iran) are non-participatory.

Weathering the Storm: Countering Bio-Weaponized Drones

Thus, in many ways, we perceive these factors as potentially contributory to a “perfect storm” wherein the increasingly widespread use of drones could obfuscate the presence of weaponized vehicles capable of delivering and disseminating disruptive – if not destructive - effects in and across a range of domains and scales.

Thus, we opine that it is – and will be ever more – vital to:

- Qualitatively and quantitatively assess and forecast if, how, and when drones could be used in such ways;

- Develop methods and tools to both prepare for such contingencies; and

- Initiate discourse to inform more stringent approaches to surveillance, oversight and regulatory control/governance of drone activity.

As we have stated before, “the sky is not falling” and exaggerative assertions and fears about the use of drones should be avoided. However, we believe that what may soon be falling from the sky warrants worry, attention, address, and prudent action to preserve national security.

The fact that at the time of writing the Pentagon announced that it will soon stand up a counter-unmanned aerial system office that will be headed by the Army is, we hope, a step in the direction to coordinating thinking and practice when it comes to countering the threat of drones internationally.